Major Ideas We’ve Covered So Far, and What’s Coming Up Next

This class asks you to think about writing a little differently than you may have in the past—or maybe just to think more than you have in the past about how writing works. We’ll be working through most of these major ideas in the first few weeks of class, and then drawing on them for the rest of the semester. This page reviews the highlights so you can, too.

When you write in university, you're not just writing for yourself--you're entering a conversation.

Imagine showing up at a party with faculty and other students. Everyone else has been here for a while already, and they're deep in conversation. You're going to need to listen for a while to figure out what's going on, and then formulate meaningful contributions to the discussion--plus support your positions and modify your claims when you learn new information from others. Eventually, you'll have to leave the party, but others will still be there--you'll need to have done your best to communicate clearly and effectively, so people remember what you said (and remember accurately what you meant to say).

(Thanks to Kenneth Burke, who articulated this idea in The Philosophy of Literary Form, 1941).

We often think we know something--until we have to explain that something in detail. Figuring out what we know and don't know is key to writing. To deal with a gap, we either need to learn the thing better, or narrow the scope of our text to something more manageable.

In the meantime, though, we “draw the bicycle” the best we know how, and refine it in later drafts!

(Thanks to cognitive psychologist Rebecca Lawson and artist Gianluca Gimini for demonstrating this idea so nicely in their bicycle projects!)

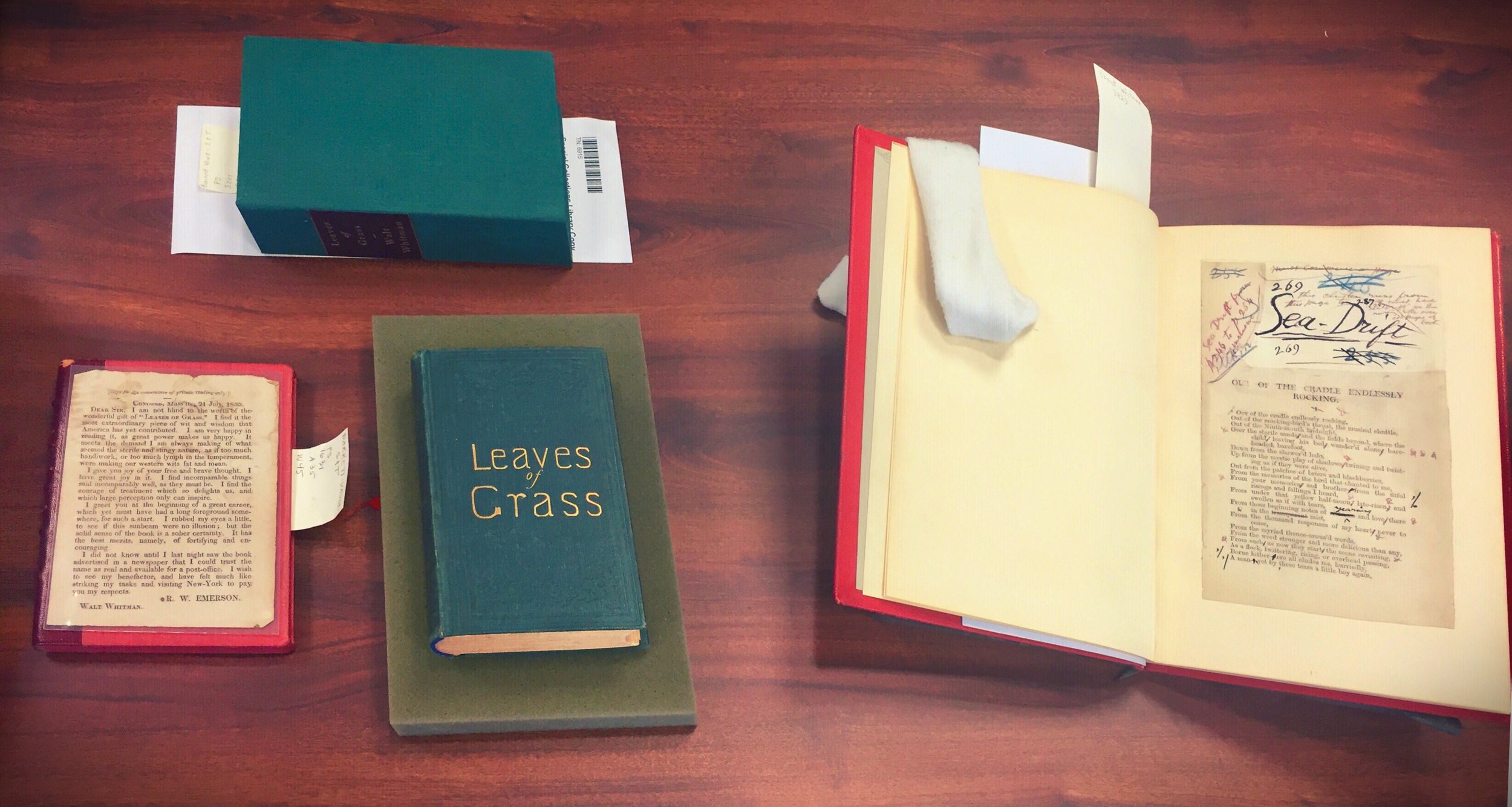

What is this document? By reading manuscript and note pages out of context, as we did in sequence over our first several class periods, we have to apply close analysis and deduction skills to sort out what we’re reading. Seeing these early notes to what we’ll learn is a prominent published book helps us understand the text more intimately than reading the public, distributed version first and alone.

Click through for photos of the displays from our time at special collections. Here is a complete materials list of everything Mr. Riser and Ms. Appiah presented for us, in case you want to follow up on anything you saw.

Any “text” is more than just the published version, as we saw in special collections. Which edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass is the “real” one? (The first edition with 12 poems? The “deathbed” edition with nearly 400 poems? One of the several iterations in between?) How do we take into account the notes, drafts, correspondence, and alternate versions associated with work by Phillis Wheatley, Mark Twain, Willa Cather, and so many others? While of course we have to eventually choose something static to read or publish for others, whatever we’ve chosen is just one moment in time for that particular text.

(Special thanks to UVA librarians Krystal Appiah and George Riser for curating this excellent exhibit and sharing their expertise with us!)

Finding Our Levels of Abstraction

Any text is some “level of abstraction” away from the foundational ideas it seeks to represent/interact with. A mind map might be a little closer to representing lots of components involved, but it usually makes most sense to you as the writer. To translate those underlying ideas to a reader, you’ll have to “abstract up”—and for the most part, every time you go up a level, you lose some precision, but gain comprehensibility. So a print ad or an infographic might be easiest for a reader to quickly read and grasp, but of course, you can’t convey everything in such a distilled format—and you could make lots of versions of those “surface structures” that all represent parts of the deeper content you care about.

So what? A few things:

As a reader, you should pay attention to the “level of abstraction” you seem to be accessing—and pay attention to what might lie beneath or conversely, how you might abstract things up (accurately!) to make them more sensible for yourself and others.

As a writer, you have to decide what level you’re working with and render a text that’s appropriate to the situation.

But also, you should know that a surface text without adequate support underneath comes across as weak or shallow—even when you can’t render ALL the things on the surface, you need to do your due diligence in research and writing to get things up there—in part because what’s underneath changes what’s on top.

Thanks to the Dept. of Humanities at the University of Utah for this helpful distillation of the science-humanities relationship.

What is “a scientific approach to artful communication,” anyway?

Writing in the sciences is technical, using specialized language and conventional representations of data. We’re reading some scientific publications this term, but we are not writing scientific publications. Instead, we’re drawing on scientific approaches including the scientific method (observation, research questions, hypotheses, testing, refine hypotheses, etc.) and RAD principles (using content that is replicable, aggregable, and data-supported) to create written materials that are substantive—that is, as much as possible, tangible, or based on tangible subjects. Art has to do with how we present and craft our material for audiences, how we interpret and create meaning with our data. We’ll revisit these ideas for the rest of the semester.

This version of the “rhetorical triangle,” as it’s sometimes called, is only one of many;

Any author, and any text, is part of a rhetorical situation—a complicated confluence of reader, author, and text in the midst of converging and diverging sociopolitical activities and forces. Authors and readers alike must account for these contextual influences in how a text will be interpreted, in what kind of life the text will have and create for others.

More highlights will appear as the course continues.

Next up: What difference does all this process stuff make, anyway?

TEMP: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1ElBrQNHGTZMr5JGf4Qi84yY0jWcg_n2h3T7H-QKAECQ/edit#gid=0